As you log out of ‘Hotmail’ you are redirected to MSN news homepage. I don’t often take much notice of the contents of the page, however, on this occasion the new Forbes listing of the richest people on the planet caught my eye.

Turns out, it was very interesting!

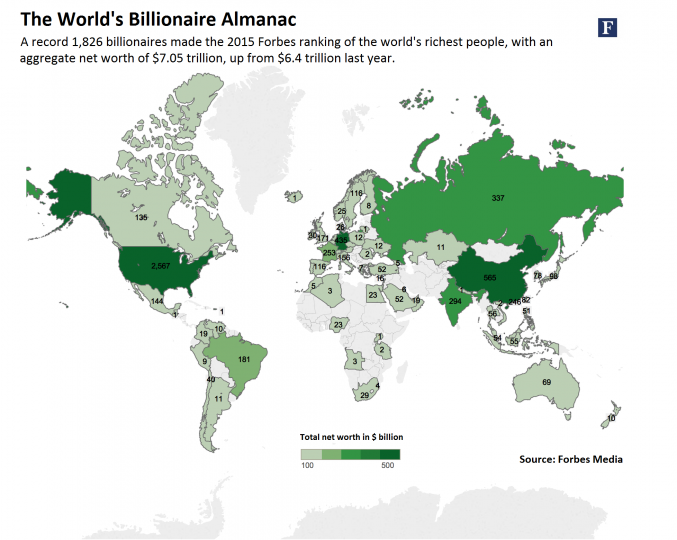

According to Forbes there are now 1,826 billionaires from 70 countries around the world. 1,187 members on the list are ‘self-made billionaires’ (so there is hope for us all yet…) the rest inherited their wealth, with some ‘adding to their inheritance.’

Collectively these billionaires are worth a net US$7.05 trillion.

Taking only the top 10 billionaires in the world, they accumulate a total value of US$556 billion with the richest man on earth Bill Gates – billionaire title holder for 16 (out of 21) years – worth a whopping US$79.3 billion.

Of the world’s 1,826 billionaires, 197 are women, and rising. But it’s still just 11% of the total number of billionaires, and just 29 of these are ‘self-made’ billionaires, the rest have inherited their wealth from their husbands or fathers, like the richest woman in the world, Christy Walton who is currently worth US$41.7 billion.

Billionaires are also getting younger. The youngest billionaire in the world is just 24! (Evan Spiegel, co-founder of photo-messaging app Snapchat). The youngest billionaire woman is Elizabeth Holmes of blood- testing firm Theranos, who is 31.

There are 819 richer billionaires than there were a year ago, while there are 519 “poorer” ones. Poor (pun intended) Aliko Dangote of Nigeria has the Forbes unfortunate title of the “biggest loser” since his fortune dropped to ‘just’ US$14.7 billion (from US$25 billion) last year. He still has the title of Africa’s richest man though.

And new into the Forbes charts is Guatemala’s Mario Lopez Estrada who became the 1,741st billionaire through the country’s mobile phone market, despite his country’s poverty.

Now why, I mused, was I so distracted with exploring the extreme wealth of others?

We relate to a society that is obsessed with wealth accumulation. Our lives are measured – and judged – by what we do and don’t have.

We are bombarded everywhere with wealth statistics, our lives measured against the likes of the Kardashian’s, the Beckhams, etc. We even have the super wealthy lecturing to us about poverty.

The strength, worth and global recognition of oneself and one’s country is based on its economic output – what the BBC have called “our apparent addiction to economic growth.”

67:3,500,000,000,000

No, the above isn’t Bill G’s credit card number. It’s what all the above means to the rest of the world.

The much publicised Oxfam International 12 page report Having it all and Wanting More revealed that, (based on 2013 figures), the 85 richest people in the world, own assets with the same value as the poorer half of the world’s population, that’s 3.5 billion people. Both groups are said to amount to US$US 1.7 trillion. That’s US$20 billion on average each, if you are in the first group, and US$486 (no I didn’t miss any zero’s) if you are in the second group.

So in wealth ‘share’ terms, in 2014, the report states that the

“richest 1% of people in the world owned 48% of global wealth, leaving just 52% to be shared between the other 99% of adults on the planet. Almost all of that 52% is owned by those included in the richest 20%, leaving just 5.5% for the remaining 80% of people in the world. If this trend continues of an increasing wealth share to the richest, the top 1% will have more wealth than the remaining 99% of people in just two years!”

This prediction is confirmed by Forbes who revised the stats with 2014 figures and reports that in just 12 months, “the rich got richer.”

In 2014 a billionaire needed an extra US$8 billion to be included in the Top 20 rich list, which reduced Oxfam’s figures from 85 billionaires to 67 that match the US$3.5 million poorest – in just 12 months!!!

According to Forbes, just these 67 people are, on average, each individually worth the same as the poorest 52 million people in the world. On his own, billionaire title holder Bill Gates, with at a net worth of US$79.3 billion has the same wealth as the poorest 156 million people around the globe. Breathtaking.

Just to put things in perspective, according to the 2014 UNDP Human Development Report, there are 1.2 billion people across 104 developing countries living on an income of US$1.25 or less a day.

2014 UNDP Human Development Report, there are 1.2 billion people across 104 developing countries living on an income of US$1.25 or less a day.

That’s measuring poverty in economic or consumption terms. However, income poverty is just part of the picture.

Issues such as poor health and nutrition, low education and skills, poor livelihoods and living conditions and social exclusion are considered in the UNDP Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), introduced in 2010. The MPI measures the proportion of people deprived and also the intensity of deprivation for each poor household.

The MPI revealed that 2.2 billion people live in multidimensional poverty or near-poverty considering these expanded realities.

Show me the money

So what does being and wanting to be wealthier make us? Well, wanting more is a concept that Professor Paul Piff took one step further and what that means to us as a society. He conducted research over nearly a decade to find out Does money makes us mean?.

His research, spanning nearly 10 years, suggests that having more money makes us increasingly self-interested and less caring of others – being wealthy can be ‘bad for your moral fibre.’ According to the Prof,

“It makes you more attuned to your own interests, your own desires, your own welfare…It isolates you in certain ways from other people psychologically and materially. You prioritise your own needs and your own goals and become less attuned to those around you…Poorer people were significantly more generous – they give 150% as much as do richer participants.”

The less money we have, the more we rely on social relationships, being wealthy makes us feel as though we don’t need others and can pay for whatever we want and feel we need.

But perhaps no-one told the Prof about billionaire philanthropy.

Back to Forbes, which lists – you guessed it – our good friend Bill (and his wife Melindah) at the top of the philanthropy ladder, having donated some US$32 billion dollars over their lifetime – about 37% of their net worth. He earns the most and gives the most away – surely there’s a lesson in this?

It seems that Bill’s philanthropy is trending, with 8 of the 67 super rich (that’s just 1,767 to go) having signed a ‘giving pledge,’ to leave the majority of their wealth to charity, with 7 of the 8 from the US, and one from India.

The amount pledged to charity comes to at least US$150 billion, assuming half of their fortunes are given away – what some 309 million people (average members of the group of 3.5 billion poorest) have today. While this won’t help the 1.2 billion people in extreme poverty now, it is, according to Forbes, designed to “create long-term change instead of alleviating immediate needs—in the long run it will help more than 300 million people.”

What it also does, it seems is create “more mobility among the richest individuals if more of the world’s richest give away their money to philanthropy, expecting future generations to start anew.” So greater competition on the Forbes richest list.

“Extreme inequality isn’t just a moral wrong. We know that it hampers economic growth and it threatens the private sector’s bottom line.” (Oxfam UK)

Given the extreme inequality throughout the world, and for the majority of us who are focused on wealth accumulation, the above statistics really should make us stop and take notice of our environment.

Are we those who are trying to keep up with the Kardashians (it used to be the Jones’ when I was younger), or are we considerate of the 2.2 billion in our midst?

In answering this question, I recommend reading the 12 page Oxfam report. It makes 9 recommendations (with a short sentence with more detail per recommendation), challenging the idea that rising inequality is not inevitable:

- Make governments work for citizens and tackle extreme inequality

- Promote women’s economic equality and women’s rights

- Pay workers a living wage and close the gap with skyrocketing executive reward

- Share the tax burden fairly to level the playing field

- Close international tax loopholes and fill holes in tax governance

- Achieve universal free public services by 2020

- Change the global system for research and development (R&D) and pricing of medicines so that everyone has access to appropriate and affordable medicines

- Implement a universal social protection floor

- Target development finance at reducing inequality and poverty, and strengthening the compact between citizens and government

Some other recommended reading:

- Read the UNDP report (or access the press summaries of the report).

- Learn about the 20 poorest countries in the world.

- Read Paul Collier’s The Bottom Billion and extracts from 80:20’s Debating Aid.

- Position yourself in this debate with Peter Singer, read the first chapter from his book The Life You Can Save (made available on the New York Times website).

Photo credit: the featured photo used on the homepage is ‘Beyond the 1%’ by Steve Corey (Sept 21, 2012) CC BY-NC-2.0 license via Flickr.